Flowers grow without any literal meaning, they are just beautiful.

— George Balanchine

Several years ago I went to New Jersey on a business trip then traveled back into New York City for the night, preparing to fly back home the next day. With some time on my hands, as the sun went down over the city, I decided to go to the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts because I'd never been there before.

Located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, the Lincoln Center is home to the New York Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Opera, and the New York City Ballet, as well as the Juilliard School. Thus, on any particular evening, they might be presenting an opera there. Or a play. Or a symphony. Or a ballet. My plan was just to get a ticket to whatever was happening that night.

I exited a yellow taxi cab under a winter-blue evening sky and took in the striking Gotham panorama all at once. The Metropolitan Opera House at the center of the plaza glowed golden through the glass of its five soaring windows. The sound and motion of a beautiful water fountain in front transported me from the bustle of the Manhattan traffic, yet still left me feeling as if I remained at the center of the world. I walked past the cascading water and into an expansive, breathtaking foyer. Symmetrically swirling, wide-curving staircases juxtaposed compellingly with the rectangular inlays of the large arched windows now behind me. Marc Chagall murals floated thrillingly on the walls like colorful clouds. A huge starburst crystalline chandelier hung above as lively theatre-goers arrived decked out in stylish clothing.

The cavernous performance space itself evoked the awe of the European opera houses I'd seen in pictures—rich woods, luxurious reds, and more starburst chandeliers hanging from the ceiling—yet at the same time the room conveyed an intriguing American modernity with its sleekly-tiered boxes scalloped five stories high. As I settled into my seat on the orchestra level, the chandeliers suddenly flashed with bursting light, then ascended magically away announcing tonight's performance was about to begin.

I was at the ballet.

I knew almost nothing about ballet and even less about George Balanchine, who choreographed this one. I was aware vaguely of his name, knowing only that he was—and this is my vernacular, not that of the elegant program I held in my hands—sort of the Babe Ruth of his art form, the 20th century's most important choreographer. After emigrating from Russia in the 1930s, he founded the School of American Ballet and trained a generation of dancers to perform his prolific work.

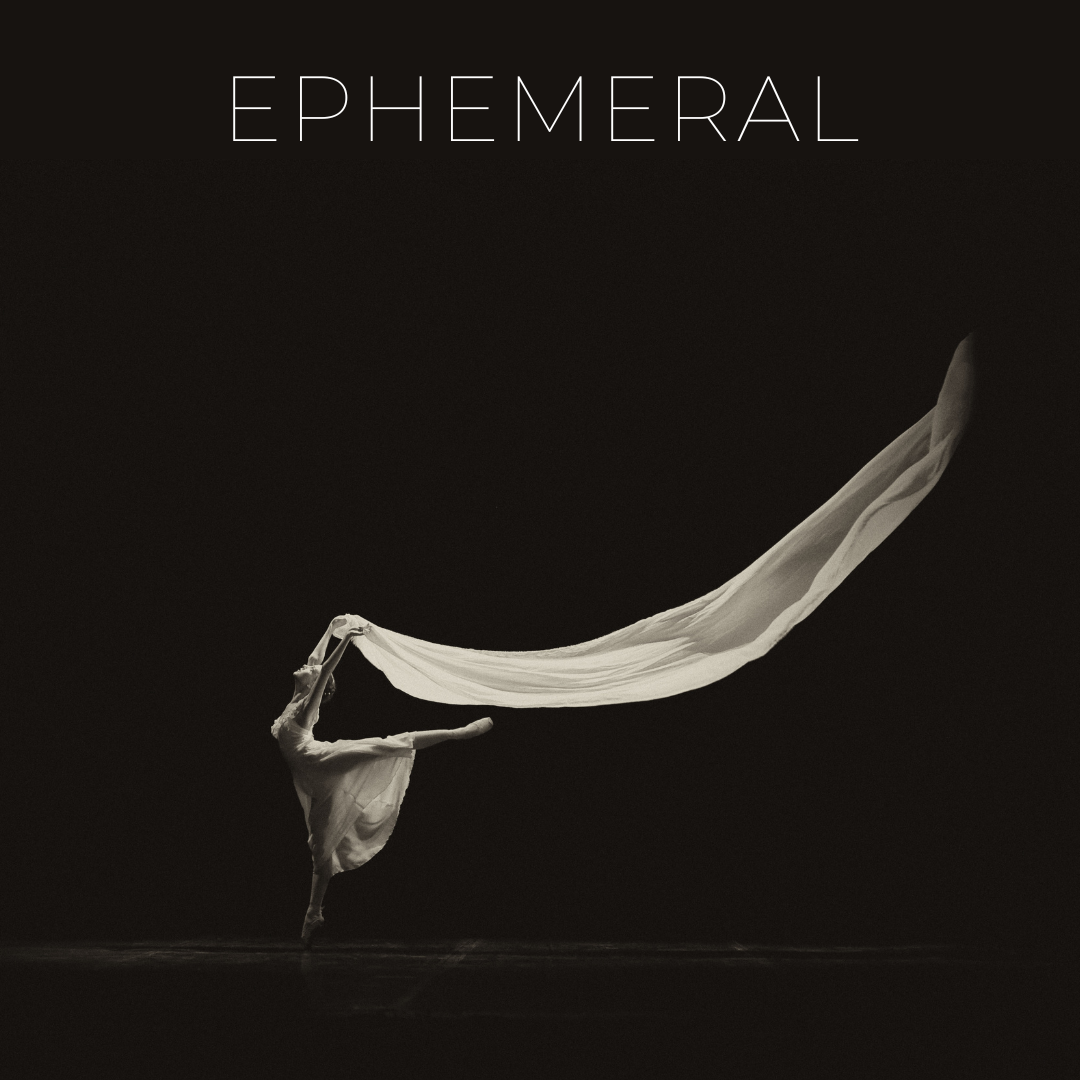

As the performance began, I found myself shaking my head in near disbelief at how the dancers had not only memorized their movements, positions, steps, and gestures, but executed them flawlessly, synchronized or in complement with one another, with both expression and precision. Without words, without voice, these athlete-artists were telling a story with only their motion, their costumes, and Balanchine's choreographic genius. While the story was soon over, even this, in the end, was beside the point.

Balanchine himself thought telling a story, offering the audience a chance to find themselves somehow in the ballet's plot, or even to gather meaning from its narrative, was secondary to simply experiencing the beauty of it. He, in fact, considered the fleeting nature of the performance central to how it conveyed this aesthetic. He often compared ballet to flowers.

"I do not believe in the permanence of anything in ballet," Balanchine once said. "When you have a garden full of pretty flowers, you don't demand of them, 'What do you mean? What is your significance?' ... Flowers grow without any literal meaning, they are just beautiful.... A flower doesn't tell you a story. It's in itself a beautiful thing."

We don't always fully appreciate beauty simply for its own sake. And we don't always comprehend the fortifying properties that even an ephemeral experience of such enchantment offers to us. We readily allow what's unlovely in the world to draw strength, vitality, and inspiration from us, but beauty is restorative. It has the power to refill us.

With a walk through a garden of flowers. In the sight of an illuminated bridge in the distance at night. Through the calming sound of tumbling water. In the way radiant architecture draws our eyes upward. In the melancholy glory of descending sunlight. In the charm of a delightful painting. In the appeal of stylish clothes. Or in the evanescence of ballet. Wherever you have the good fortune to encounter it, let beauty revitalize you, reenergize your capacity to love, and renew your aspirations to embody grace and beauty itself.

God — Restore me with beauty. Amen.

— Greg Funderburk