Earth's crammed with heaven,

And every common bush afire with God;

But only he who sees, takes off his shoes,

The rest sit round it and pluck blackberries....

— Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh, Book 7, 1857

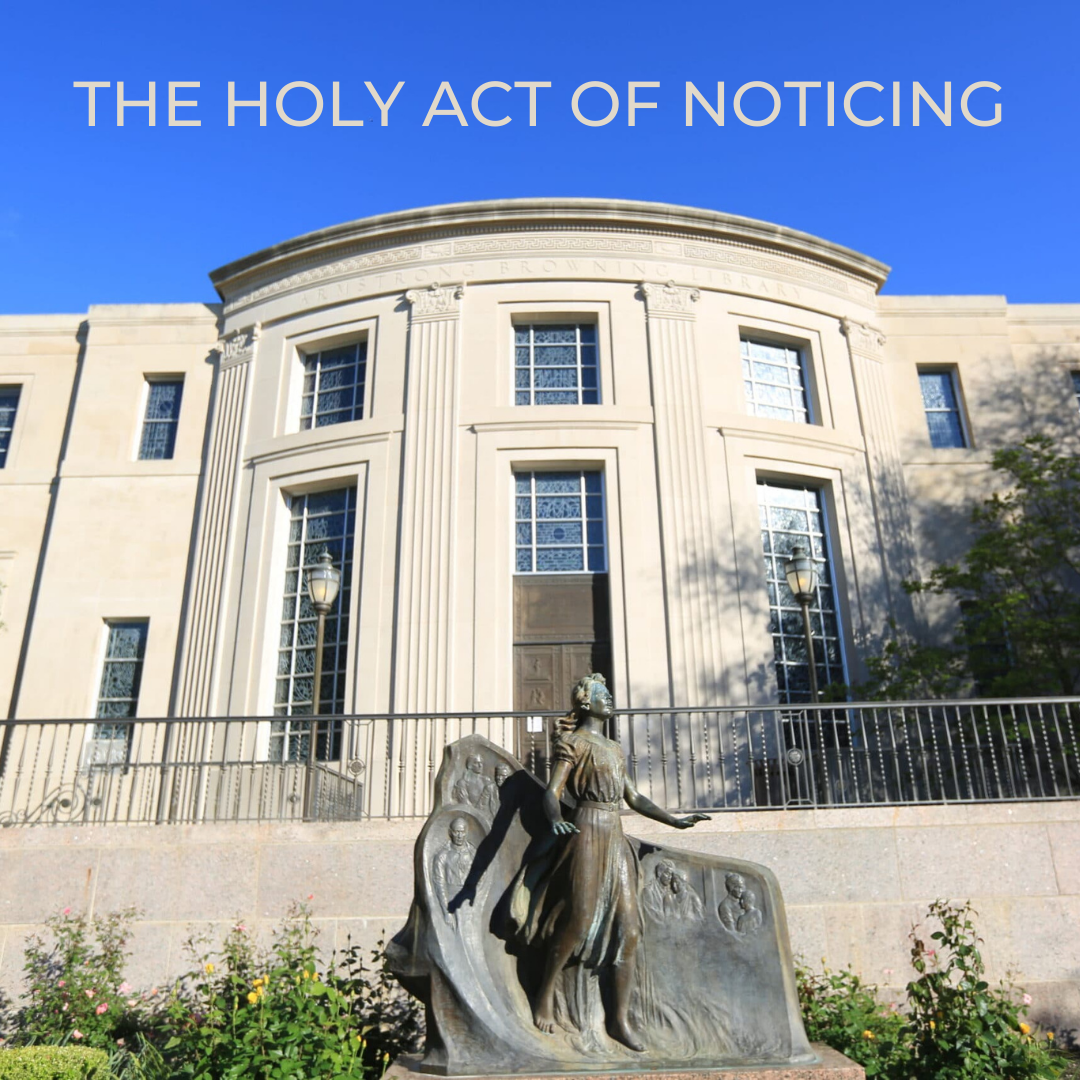

One of the many things I'd do if I were able to rerun my college experience would be to spend more time inside the Armstrong Browning Library on the campus of Baylor University. My dad first pointed the building out to me when I was eight as we watched a parade of colorful and amusing floats roll down Speight Avenue before the Bears' homecoming game. I was intrigued by the library's regal look and wondered just who this Armstrong and Browning might be. Not too terribly long after that, as a student there, I passed by the impressive structure regularly on the way to classes, but somehow I only found my way inside once or twice.

The beautiful building was the lifelong dream of Dr. A.J. Armstrong, who chaired Baylor's English Department from 1912 to 1952. Construction began in 1948, and now the library houses the world's largest collection of original letters, manuscripts, and books related to the Victorian poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, much of it procured during the early part of the 20th century by Armstrong and his wife, Mary, and with the help of the Browning's only son, Pen.

If I ask myself now why I didn't take advantage of all the library had to offer back then, the practical answer was that I wasn't an English major, so it sort of felt off limits. The granite steps, the vibrant stained glass, the rich walnut interiors, the intricacies in the ceiling, the brass inlays within the terrazzo floors, the particularly academic brand of silence that swelled inside—it all seemed well above my station as a young undergrad. Maybe it was, but I shouldn't have missed it so entirely, as the Brownings are perhaps the most accomplished literary couple of all time. And there—at the corner of 8th & Speight—one can actually examine the penmanship of their romantic correspondence, analyze original manuscripts of their poetry, hold in one's hands a number of first editions of their books, and look through untold volumes of material from their personal libraries.

Though it's Robert Browning's bones that are interred under the slate in Poet's Corner at Westminster Abbey, most experts agree that Elizabeth's lifetime of work far surpasses his. She's perhaps best remembered for the line, "How do I love thee, let me count the ways," which she wrote to him during their courtship. But just a few years after unleashing her stirring sonnets into the world, she published a novel-length epic poem called Aurora Leigh, "into which" she said, "my highest convictions upon Life and Art have entered." It is in Aurora Leigh, that Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote:

Earth's crammed with heaven,

And every common bush afire with God;

But only he who sees, takes off his shoes,

The rest sit round it and pluck blackberries....

What other Victorian poet would select the unpretentious, even indelicate, yet muscular word "crammed" here to express such a sacred thought, then juxtapose it with a Biblical example, a Mosaic reference concerning what could be called the holy act of noticing. Ancient rabbinical commentaries on Exodus written in Hebrew (which by the way was a language Elizabeth learned to read as a teenager along with Latin, Greek, and Italian) point out that the burning thing, which Moses came upon in the wilderness, was not a large tree but a simple thorn bush. That is to say, this was not a high-production-value miracle or sublime divine appearance. It was a shrub on fire—with no real need for Moses to pay it any mind. Some rabbis suggest it may have even taken him days to realize the bush was not being consumed before he turned aside from his everyday shepherding duties to notice the "common bush afire with God," but when he did, it changed everything. Soon he was barefoot in the sacred presence of Yahweh.

We miss a lot. We daily walk by remarkable things like the one at the corner of 8th Street and Speight Avenue in Waco. There are places we fail to enter. Everyday wonders with which we fail to engage. We miss that the earth is crammed with heaven. If we'd just notice it, we might come to recognize, we're always on holy ground. Maybe it would help if every once in a while we took off our shoes, looked around, and let ourselves become astonished.

God — Today, let me not miss it. Amen.

— Greg Funderburk